By Jennifer Fletcher

In other posts (see here and here), I’ve written about the value of dialogic argumentation as a mainstay of intellectual work. This is the “they say, I say” approach to source-based writing described by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein in their popular little book by the same name. Understanding and responding to what others say is our bread and butter in academia. This is how all intellectual work gets done; we listen and learn from the field, figure out what’s already been done, identify needs and gaps, and make our own contributions. We move from “they say” (i.e, listening, reading, understanding) to “I say” (i.e., analyzing, evaluating, arguing).

“That’s Not What I’m Saying”

As clear and common as this model is, however, it seems that getting the “they say” of a conversation right is an increasingly rare occurrence, at least in the world of public discourse. Understanding before arguing now seems a custom more honored in the breach than the observance.

Think of a time you when you told someone (or wanted to tell someone), “That’s not what I’m saying.” My oldest child said this to me just the other day. He was talking about his grandparents’ senior living community and said, “I don’t even know if there will be retirement homes for my generation.” I joked, “I don’t think humanity will end before you retire,” and my son calmly looked at me and said, “That’s not what I’m saying.” Of course it wasn’t, and I immediately regretted my flippancy. He explained that his point was about declining life expectancy, not the apocalypse.

Inaccurate paraphrases are not always so gently met. It can knock the wind out of us when we work hard to make ourselves understood only to have our views misrepresented. All humans have a profound need to be heard. When someone overstates or oversimplifies our messages or mischaracterizes our intentions, we feel silenced.

Understanding is also a precondition for finding common ground and hence for collective action. We don’t know what cares and concerns we share with others if we don’t understand they’re saying.

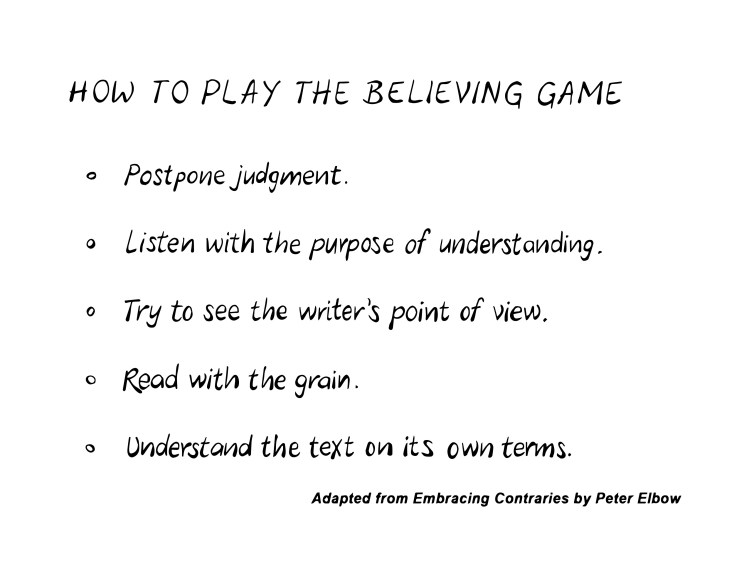

Treating Paraphrase and Summary as Prerequisite Skills

Paraphrase and summary are thus some of the most important academic literacy skills we teach. These are gateway competencies if our goal is to promote effective communication and problem solving. I’ll put paraphrase and summary ahead of a skill like rebuttal in my list of teaching priorities any day. Before students learn to rebut others’ arguments ( in those cases in which rebuttal is an appropriate move), they need to learn to understand arguments on the writers’ own terms. And beyond understanding others’ perspectives–and recognizing that these perspectives represent the lived experiences of real individuals–students also need to be able to situate those perspectives within an ongoing conversation and within the context of their own arguments. So synthesis makes my list of instructional priorities, too.

Hosting the Conversation

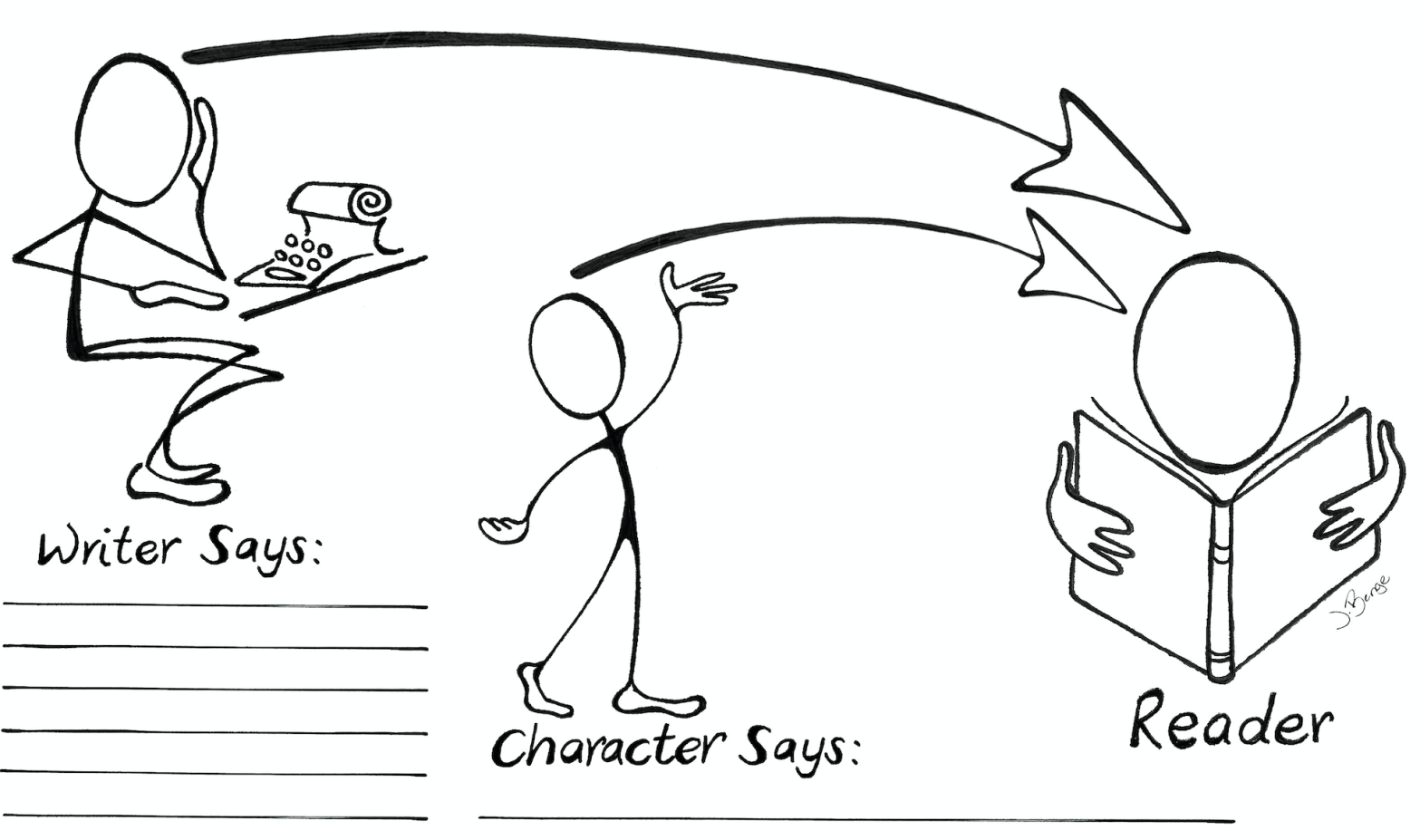

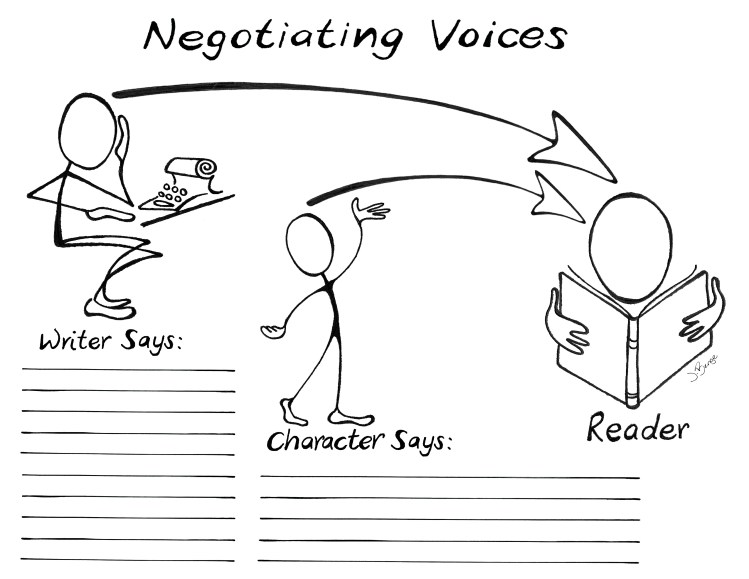

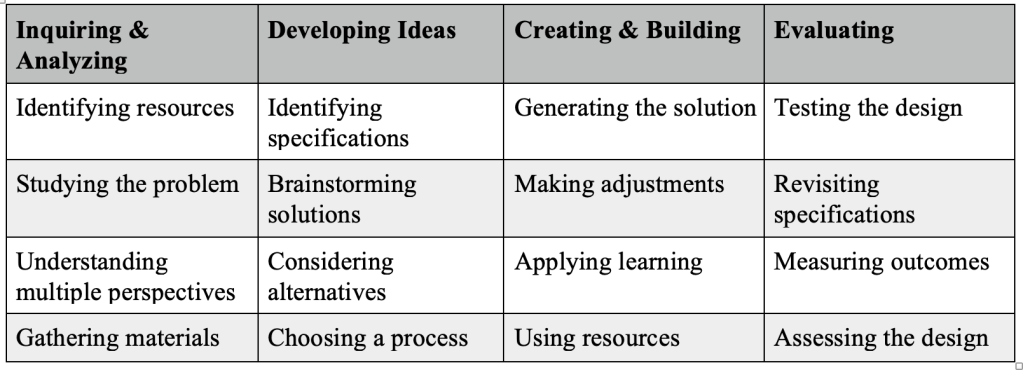

The three ways of using the words of other writers that form the basis of source-based writing—direct quotation, paraphrase, and summary—can be thought of as three interpretive strategies. In other words, they are tools for figuring out who is saying what. Each citation method has different rhetorical functions:

- Quotation showcases a source’s language choices when those choices matter.

- Paraphrase seamlessly integrates a source’s content with a writer’s argument.

- Summary offers a “big picture” of a source’s main ideas or importance.

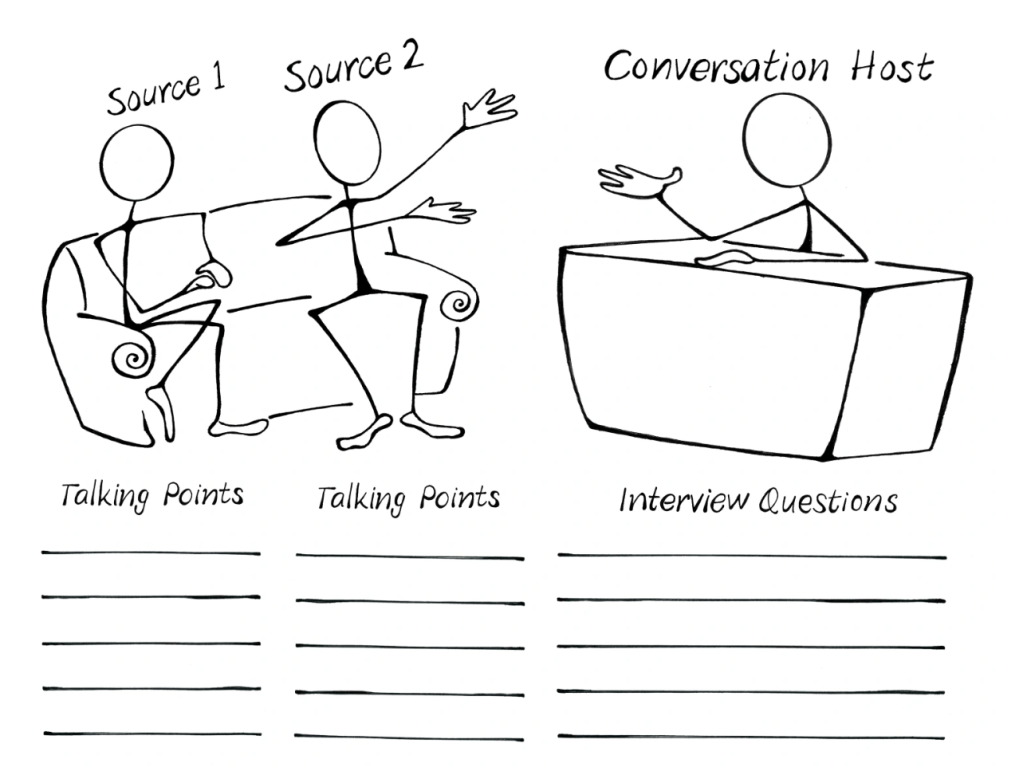

In Writing Rhetorically, I explain these differences through the analogy of a talk show. When we write using sources, we act as “conversation hosts” who invite others to join the discussion and share their perspectives. Our “guests” are the sources we cite in our compositions. I invite students to prepare for their role as hosts by creating “Conversation Planning Notes” based on key sources.

Quote, Paraphrase, or Summarize?

In a direct quotation, the host (i.e., writer) passes the mic to the guest (i.e., source), so they can speak for themself. A paraphrase, on the other hand, is a bit more like a mention in a monologue. The host says, “So I was talking to so-and-so the other day . . .” and then relates what the person says. But only the host gets to stand in the spotlight.

Paraphrase is an important way to check for understanding; it is an “imitation or transformation” (Rabinowitz 17) of another person’s meaning. Paraphrases can differ significantly from the original text but still adequately demonstrate understanding. In the landmark work Before Reading: Narrative Conventions and the Politics of Interpretation, Peter Rabinowitz gives the example of a parent who says, “It’s time for bed,” and a child responding, “Is it really eight o’clock?” (16). While the child’s paraphrase is not synonymous with the parent’s statement, it nevertheless demonstrates that the child understands what they have been told.

What counts as an adequate paraphrase? An adequate paraphrase fairly and responsibly represents a person’s meaning. There’s a moment in the 2017 Lego Batman Movie that struck a chord with me. See if the following dialogue rings any English teacher bells for you, too:

Batman: We are gonna steal the Phantom Zone projector from Superman. Robin: [frowns] Steal? Batman: Yeah. We have to right a wrong. And sometimes, in order to right a wrong, you have to do a wrong-right. Gandhi said that. Robin: Are we sure Gandhi said that? Batman: I’m paraphrasing.

A colleague of mine says, “You can make a square peg fit into a round hole, but you have to do violence to the peg.” Ethical communicators don’t do violence to their sources to make them fit their arguments.

Summary Writing

Summary sits just outside the live discussion. While it doesn’t offer the immediate back-and-forth exchange of direct quotation or the specificity of paraphrase, summary does provide the deep understanding of a writer’s contributions that justifies why that writer was invited to join the conversation in the first place.

Developing a habit of effective summary writing is one of the best ways to become an informed writer. I used to think summary writing was a low-level activity analogous to a book report. And then I started reading my students’ summaries instead of just checking them for completion. There’s nothing easy about trying to capture the truth of a whole work. “Good summary writing,” composition scholar Charles Bazerman says, “requires careful attention to the meaning and shape of the entire text,” cautioning that “much meaning can be distorted or lost by too rushed a summary” (77).

Obstacles to Understanding

Paraphrase and summary writing are especially difficult when a text contains both complex language and new ideas. A text such as Audre Lorde’s “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action” (a speech we use in a high school curriculum in California) makes heavy cognitive and linguistic demands on readers. When complex texts also contain what researchers have called “troublesome knowledge,” that is, ideas that are particularly difficult for novices to understand, students will have to do even more work before they’re ready to summarize the text.

Jan Meyer and Ray Land’s work on threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge explain how students encounter not only cognitive and linguistic demands but also epistemological challenges when a text presents a way of knowing that differs from their own. Threshold concepts are counter-initituitive, transformative, and difficult to unlearn.

For example, for people used to thinking about power in hierarchical terms, French philosopher Michel Foucault’s conception of power as a multi-directional network of interconnected social relationships can be difficult to grasp. In Foucault’s model, power doesn’t just move up and down; it circulates pervasively. Understanding Foucault on his own terms (what we aspire to do when we paraphrase a writer responsibly) might mean letting go of centralized and stratified ways of seeing power.

Before I’m prepared to responsibly paraphrase the claims or summarize the theory of a scholar like Michel Foucault, I might need to undergo some radical reorientations in my own thinking.

Getting It Right

It bears repeating that effectively communicating across our differences is one of the hardest things we do. We know from the past couple years of virtual work and distance learning that it’s hard to respond fully to other humans when all we see is a little box on a screen. Written texts likewise require us to imagine more than we can see with our eyes: to see sources as real people, to experience other worldviews, and to enter other ways of being. Treating paraphrase and summary as the foundational skills they are gets us closer to bridging our differences.

Jennifer Fletcher is a professor of English at California State University, Monterey Bay and a former high school teacher. You can contact her at jfletcher@csumb.edu or on Twitter @JenJFletcher.

Works Cited

Bazerman, Charles. The Informed Writer: Using Sources in the Disciplines. 5th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

Fletcher, Jennifer. Writing Rhetorically: Fostering Responsive Thinkers and Communicators. Stenhouse, 2021.

Graff, Gerald and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say, I Say. W.W. Norton, 2021.

Meyer, Jan .H.F and Ray Land. Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge. London: Routledge, 2006.

Rabinowitz, Peter J. Before Reading: Narrative Conventions and the Politics of Interpretation. Columbus: Ohio State University, 1987.