By Jennifer Fletcher

I had a revelation the other morning while feeding coins into one of our university’s parking meters: Shortcuts keep you stuck in survivor mode. You might be wondering why, in 2024, I’m paying for parking with loose change. “Isn’t there an app for that?” you might justifiably ask. Or better yet, you might question why I don’t have a campus parking permit. After all, I’m faculty at this university.

Here’s the deal: I would have the app or the permit except I couldn’t quite get my act together before the semester started. My iPhone 8 is too full of data to add new apps without deleting old ones first, and a parking permit means searching through my in-box for that email from Parking Services I never responded to. Late and rushing to get to class, I figured it’d be faster and easier to dig quarters out of my car than to take the extra time to do things the right way.

The Temptation of Speed and Efficiency

In our lives as writing teachers, we’re also often tempted–and even encouraged–to find a fast and easy way out of difficulties. But just like my scramble to pay for parking, quick-fix writing hacks don’t lead to long-term solutions. They’re also a sign of a writer (or teacher) who is stuck in survivor mode.

In The Writing Is What Matters, John Warners says, “We have to be careful not to fall into the trap of privileging speedier outcomes over the experience of the journey.” Warner argues that valuing product over process “can steer us away from quality.” When the grade or the deadline is all we can see, we downshift to a less engaged and organic method of working. Expediency takes precedence over creativity and expression. Getting it done becomes more important than getting it right.

Warner says he fights this battle in his own life as a writing teacher, which is why he’s moved to labor-based grading contracts:

The great challenge I’ve experienced in teaching writing is in trying to get students to embrace these intrinsic rewards that come with deep engagement driven by one’s own fascinations. Unfortunately, the system we all work within places much greater value not on the doing but the having done—the object, not the process.

“The Writing is What Matters” by John Warner, published in Inside Higher Ed

The educational system we work within, as Warner notes, continues to pressure students and teachers to deliver quantifiable results in strict timelines, primarily through high-stakes testing. This is something Arthur N. Applebee and Judith A. Langer have researched at length. In Writing Instruction that Works: Proven Methods for Middle and High School Classrooms, Applebee and Langer conclude that “the importance placed on these exams does not auger well for the teaching of writing” (16). The testing and accountability movement, according to Applebee and Langer, have the combined effect of narrowing what gets taught and how it’s taught.

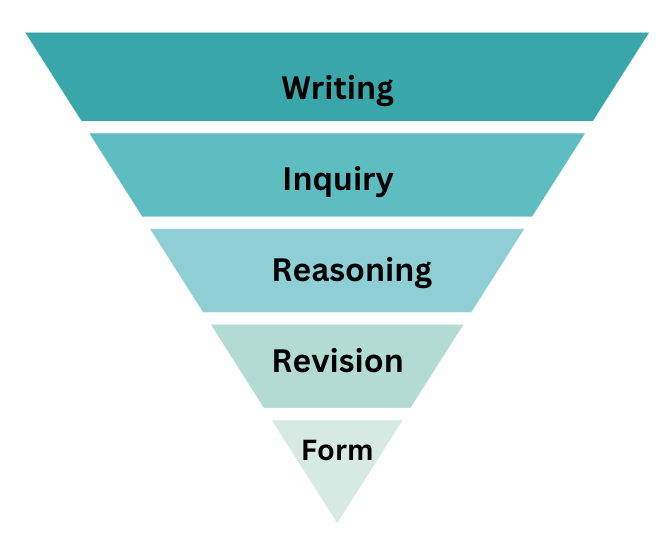

In the case of writing, what often doesn’t get taught are the inquiry, reasoning, and revision processes that require significant instructional time and curricular space. Timed-crunched, test-pressured teachers frequently turn to formulaic instruction as a way to accelerate the learning cycle. The fastest way to get students to write a complete, “proficient” essay is to tell them step-by-step what to do. And our students–who daily cope with novelty and stress in their school lives–are often happy to have the burden of invention taken away from them. A shortcut to apparent proficiency is an escape route from discomfort.

There’s also this: It’s hard to develop revision skills if you skip the inquiry and drafting process. An authentic iterative composing process creates a big mess that needs to be cleaned up. A fill-in-the-blank template doesn’t.

From Coping to Learning

Decades ago in my teaching credential program, I learned to recognize the differences between coping strategies and learning strategies from Dr. Maria Montaño-Harmon at Cal State Fullerton. I’ve since synthesized what I’ve learned about coping mechanisms in K12 students with research on novices from scholars such as Jan Meyer, Ray Land, and Patricia Benner. Novices cope with the difficulties of being a novice by doing the following kinds of things:

- Seek and follow rules and formulas

- Substitute an easier task for a more complex task

- Rush to finish a task

- Use a checklist to determine when a task is complete

- Rely on acronyms to remember procedures

- Bluff their way through a task

- Cheat or plagiarize

- Use AI when they’re not sure what to do

These are a novice’s survival strategies. Beginners naturally seek ways to deal with the stress of inexperience, uncertainty, and self-doubt. Our job as teachers is to help students grow beyond the novice stage.

The Cost of Shortcuts

The cost of product-centered, efficiency-focused instruction is that it perpetuates the novice stage for learners. When we devalue process, coping strategies seem like just the way to do school. Classes become something to survive, not enjoy.

Consider the familiar example of the five-paragraph essay, a genre developed in response to high-stakes testing. The 5PE is one of those shortcuts to proficiency that works against student agency and growth by interfering with students’ ability to make rhetorical choices. Writing scholars Nigel A. Caplan and Ann M. Johns have this to say about this highly formulaic essay structure: “What defines the five-paragraph essay is …an approach to writing that is insensitive to context, rhetorical situation, audience, or communicative purpose” (vi). This approach, Caplan and Johns argue, is grounded in “the mistaken belief that any writing task is a problem that can be solved by applying the same formula” (vi).

Rather than solving the problem of how to write, quick-fix formulas just put off the day when students will have to figure out how to make choices for themselves. Following a formula might work for an individual assignment or test, but it doesn’t lead to deep and transferrable learning.

Privileging Process Over Product

In contrast to product-based scaffolds like the 5PE, process-based scaffolds empower students to make their own choices and mistakes. Scaffolds for supporting inquiry work–such as quickwrites, collaborative discussion, or the study of mentor texts–allow students to learn by trial and error. Does this take more time? Sure. It also requires a high tolerance for uncertainty and failure. An untethered writing process takes on a life of its own that can lead to as many dead-ends as breakthroughs. When we privilege process over product, however, “failure” becomes just another name for something that didn’t work, rather than a mark in a grade book.

Shortcuts to the final product, on the other hand, short circuit the critical research, reasoning, and writing processes that develop students’ independence and creativity.

What Matters

We all have times in our lives when we’re just coping–e.g., me at the parking meter fumbling with coins and praying to be on time for class. I resort to coping strategies more often than I’d like. But when I do, I’m aware that I’m not thriving in those moments.

As a teacher, I also know that I’ve done my students a disservice if all they take away from my class is more experience coping with the frustrations of school instead of the joyful rewards of learning for the sake of learning. Warner puts it nicely: “When it comes to writing, what matters is the writing. When it comes to learning, what matters is the learning.”

Jennifer Fletcher is a professor of English at California State University, Monterey Bay and a former high school teacher. She is the author of Teaching Arguments, Teaching Literature Rhetorically, and Writing Rhetorically.

Works Cited

Applebee, Arthur N. and Judith A. Langer. Writing Instruction That Works: Proven Methods for Middle and High School Classrooms. Teachers College Press, 2013.

Benner, Patricia. “From Novice to Expert.” The American Journal of Nursing, vol. 82, no. 3, 1982, pp. 402–407. JSTOR, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3462928.

Caplan, Nigel A. and Ann M. Johns. Changing Practices for the L2 Writing Classroom: Moving Beyond the Five-Paragraph Essay. University of Michigan Press, 2019

Meyer, Jan .H.F and Ray Land. Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge. Routledge, 2006.

Warner, John. “The Writing Is What Matters.” Inside Higher Ed. 01 Feb. 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/blogs/just-visiting/2024/02/01/process-all-learning-through-writing.

Note: This spring I’m delighted to be facilitating an online course for the National Writing Project on teaching arguments rhetorically. In case you didn’t know, this year marks the 50th anniversary of NWP. No one does process better than the Writing Project or more fully exemplifies the idea that the writing is what matters. I hope you’ll consider joining me for this spring course.

Here are the details:

Course Description: Deepen your students’ understanding of how to analyze and compose arguments in diverse situations! When we teach argument writing rhetorically, we empower students to make their own choices as thinkers and communicators. A rhetorical approach cultivates adaptive, independent learners who can discover their own questions, design their own inquiry process, develop their own position and purposes, and contribute to conversations that matter to them.

This four-week course facilitated by author and teacher Jennifer Fletcher provides strategies and frameworks for taking argument writing to the next level by developing students’ rhetorical problem-solving skills. These include the dialogic and analytical skills that help learners communicate and collaborate across contexts. Using examples from Jennifer’s book, Writing Rhetorically, participants in the course examine and design instructional activities that foster inquiry-based argumentation and transferable literacy skills.

Note that there is a eight-week break between Session 1 and Session 2 of this course to allow participants time to apply and reflect on their learning.

NOTE: The registration fee for this course includes a copy of Writing Rhetorically: Fostering Responsive Thinkers and Communicators

What You Will Get:

- Four real-time virtual workshops with author and teacher Jennifer Fletcher

- A print copy of Writing Rhetorically: Fostering Responsive Thinkers and Communicators

- Digital study guide and appendixes for Writing Rhetorically and Teaching Arguments

- Activities and graphic organizers for teaching audience, purpose, genre, and structure

- Support for teaching evidence-based reasoning, synthesis, and claim development

- A digital badge indicating completion of 20 learning hours

- Option for 2 CEUs through CA State University, Monterey Bay for an additional cost.

Time Commitment

This course will run for two weeks in March and two weeks in May of 2024:

- March 3 – 16, 2024

- Real-time events: March 6th and March 13, 4-5pm PT | 7-8pm ET

- May 5 – 18, 2024

- Real-time events: May 8th and 15th, 4-5pm PT | 7-8pm ET

- 1 hour of synchronous and four hours of self-paced learning per week for a total of 20 hours

For questions and other payment options, email teachargument@nwp.org

For more about courses offered here by NWP: https://www.nwp.org/courses