By Jennifer Fletcher

Tertullian credo ut intelligam [I believe in order to understand].

(quoted in Writing Without Teachers by Peter Elbow)

I can’t decide if this is brilliant or silly. But here’s the latest way I’ve been trying to teach students how to play Peter Elbow’s believing game, a strategy for understanding a text or perspective on its own terms. In Writing Without Teachers, Elbow offers a striking analogy for the active and open-minded listening foundational to comprehension:

“Listen to what they say as though it were all true. The way an owl eats a mouse. He takes it all in. He doesn’t try to sort out the good parts from the bad. He trusts his organism to make use of what’s good and get rid of what isn’t.”

(Elbow 102-3)

Somehow in my twenty years of teaching Elbow’s doubting and believing game (see my approach), I’d never encountered this graphic comparison before. It’s as apt as it is arresting. This was a new way for me to understand what Elbow means when he says, “Believe all the assertions” (Elbow 148). According to Elbow, picking out just those assertions that seem truest would be the guessing game, not the believing game (148).

Taking It All In

Refraining from doubt is not a passive activity. Active belief requires hard work. We have to ask ourselves, “What do I have to believe, hold true, or value in order to make connections between the writer’s evidence and assertions?” And then we actually have to perform the mental operations necessary to make those connections. This isn’t easy.

Elbow’s owl got me thinking: What if the argument we’re trying to swallow is more than a mouse? What if it’s more like a hedgehog? Are there various degrees of difficulty in the believing game? Are there special strategies we can use when we need more processing time to deal with the amount of indigestible material we’ve just taken in? When a position is particularly unpalatable, how do we practice getting it down in a gulp so we can start digesting its evidence and reasoning?

Let me be clear that I’m not talking about the kind of suspension of disbelief that causes harm to ourselves and others or that treats the validity of people’s experiences and identities as a suitable topic for classroom debate. As many who teach for justice remind us, personal experience is not up for debate.

Sometimes the visceral rejection we feel for a text is essential for self-preservation. But other times we can grow and learn by coaching ourselves beyond our initial gut reaction to a viewpoint we might not like. The ability to distinguish between toxic viewpoints and healthy intellectual debate is essential to critical thinking.

It also helps to know that, like an owl, we can keep what we can use and let go of the rest–but only after we’ve worked to understand a text on its own terms first. The ultimate purpose of the believing game, like its counterpart the doubting game, is to discover truths by indirection (Elbow 148).

Making Belief a Game

In calling this literacy practice a “game,” Peter Elbow spotlights methodological belief as a tool for making decisions about texts and issues. The tool can’t do our thinking for us, but it can help us develop greater intellectual sophistication by giving us more (and more unusual) pathways to understanding. Elbow’s method requires a kind of rhetorical imagination that allows us to inhabit ways of knowing and being that might feel alien to us.

It’s important to remember that this kind of provisional belief is a game, not a commitment. We’re not pledging ourselves to a stance that doesn’t represent who we are or what we value. We’re momentarily slipping through the looking glass in an effort to see from a different perspective. The game is an exercise in believing what seems counterintuitive, disorienting, or even impossible to us. That impossibility is our safety net. We temporarily suspend our disbelief, knowing we can return from Wonderland when we’re ready. Like Lewis Carroll’s White Queen, we can learn to believe (or, at least, imagine) the impossible through extended practice:

“Alice laughed: ‘There’s no use trying,’ she said; ‘one can’t believe impossible things.’ ‘I daresay you haven’t had much practice,’ said the Queen. ‘When I was younger, I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.’

from Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll

Carroll may have been satirizing absurdities, but the idea of building our capacity for belief is important. To actively believe, we have to be willing to go into another world and dwell there for a while.

Building Your Believing Muscle

Say you’re listening to a sales pitch that turns a little too slick. Here’s an opportunity to build your believing muscle. This doesn’t mean you have to buy the timeshare. It means that, for the moment, you flip the switch that allows you to imagine what it would feel like to believe the speaker’s message. To do this, we must turn off the alert skepticism that has been activated by the sales pitch.

Of course, many of the rhetorical situations we face are more nuanced than a hard sell. Often, we flicker between belief and doubt unconsciously. Turning our natural capacity for doubt and belief into an intentional literacy strategy takes effort and practice.

Here’s an activity to try with your students that can build their believing muscle. Show them the claim and photo that follow:

CLAIM: THERE ARE NO ANIMALS IN THIS PHOTO.

Then ask, “What do you have to do to believe this statement?” Invite students to discuss their thought process with a partner or small group. Record responses on chart paper or in a shared doc. In my classes, students have said that they have to do the following things to believe this claim:

- Read the claim carefully

- Activate and then deactivate prior knowledge (“forget what you know”)

- Define “animal”

- Define “photo”

I follow up this discussion by asking students to make a list of 3 strategies for playing the believing game. Here are some of the strategies they’ve generated:

- Trust the author

- Change your perspective

- Suspend disbelief

- Set aside your feelings

- Use the author’s terms and definitions

- Stay focused on understanding, not judging

Believing Is Seeing

Elbow compares the attempt at belief to the experience of seeing a distant animal in a landscape and not knowing what it is. Through the act of believing–“I think that’s a dog”–we start to see details we couldn’t see before (162-163). “That must be the dog’s tail and ears,” we think, though at first glance the animal was just a blur. Elbow explains how believing is seeing:

“By believing an assertion we can get farther and farther into it, see more and more things in terms of it or ‘through’ it, use it as a hypothesis to climb higher and higher to a point from which more can be seen and understood…”

(163)

Believing in Bigfoot

A fun way to build on this idea with students is by exploring images of purported paranormal activity. In the case of Big Foot or UFOs or the Loch Ness Monster, if you don’t believe it, you for sure can’t see it. I’ll show students a forest scene with some fuzzy details and ask if they can see Big Foot. Eyes widen and interest spikes.

“For real?” they ask.

“Maybe,” I shrug.

They start looking. That blur behind the tree–is that a shadow? A bear? An unshaved hiker? Some are convinced they see something out of the ordinary. After a while, I confess that the photo is just a stock image of a forest and I have no idea whether Big Foot actually frequents this wilderness or even exists. Then I make my point: You have to allow yourself to believe in Big Foot, at least temporarily, in order to look for Big Foot. Belief is part of the inquiry process. If you don’t find Big Foot, that provisional belief might ultimately lead to the conclusion that Big Foot isn’t real.

Try sharing the following image with your students and asking this question: What would you have to do to (temporarily) believe the claim that “Big Foot” has been sighted in the area?

Here’s another one to try. Look at the following image. What do you see?

What if I tell you this is a photo of a UFO? Can you see it now, or at least something that sorta looks like a UFO? Even if you quickly dismiss this idea as impossible or highly unlikely, for a moment you saw it, right?

Leveling Up with Validation Strategies

Taking it all in includes taking in the writer’s or speaker’s feelings, experiences, and humanity. Next-level believing game skills include techniques for validating diverse perspectives. Validation is not agreement. Validation is an affirmation of a person’s humanity–of their human emotions and lived experiences. Once students have some initial practice playing the believing game, I encourage them to take the extra step beyond paraphrase or summary toward validation.

Understanding Plus Validation

What does validation feel like? What does validation do in a rhetorical situation, especially one fraught with tension and division? Acknowledging people’s emotions changes the energy in a conversation. Think about the transformative potential of validation as you read these strategies for validating a perspective:

- Name the emotions the person seems to be feeling

- Acknowledge their right to feel those emotions

- Remember that feelings aren’t thoughts or actions

- Honor the person as the expert on their own experience

- Look at the world through the person’s eyes

- Accept that person’s reality

You can also share validating statements with your students to use during the believing game:

- That must be really frustrating/upsetting/frightening/etc. for this person.

- I can see how important this issue is to this person.

- I can tell from this person’s words that they’re feeling angry/sad/happy/confused/etc.

- I can see how hard this person is trying to solve the problem.

The longer we sit in that validation space, the deeper our understanding of the context and complexities of an argument.

Mouse or Marmot?

Eventually, we do get to spit out the stuff we can’t absorb into our own way of thinking (I know, the owl metaphor just keeps getting worse). Some “pellets” will be bigger than others. You could even invite your students to classify the claims and evidence they ultimately can’t accept after working through a full rhetorical reading of an argument by noting the reasons for and extent of the argument’s “indigestibility.” Are there just a few little mouse bones leftover? Or a full marmot skeleton?

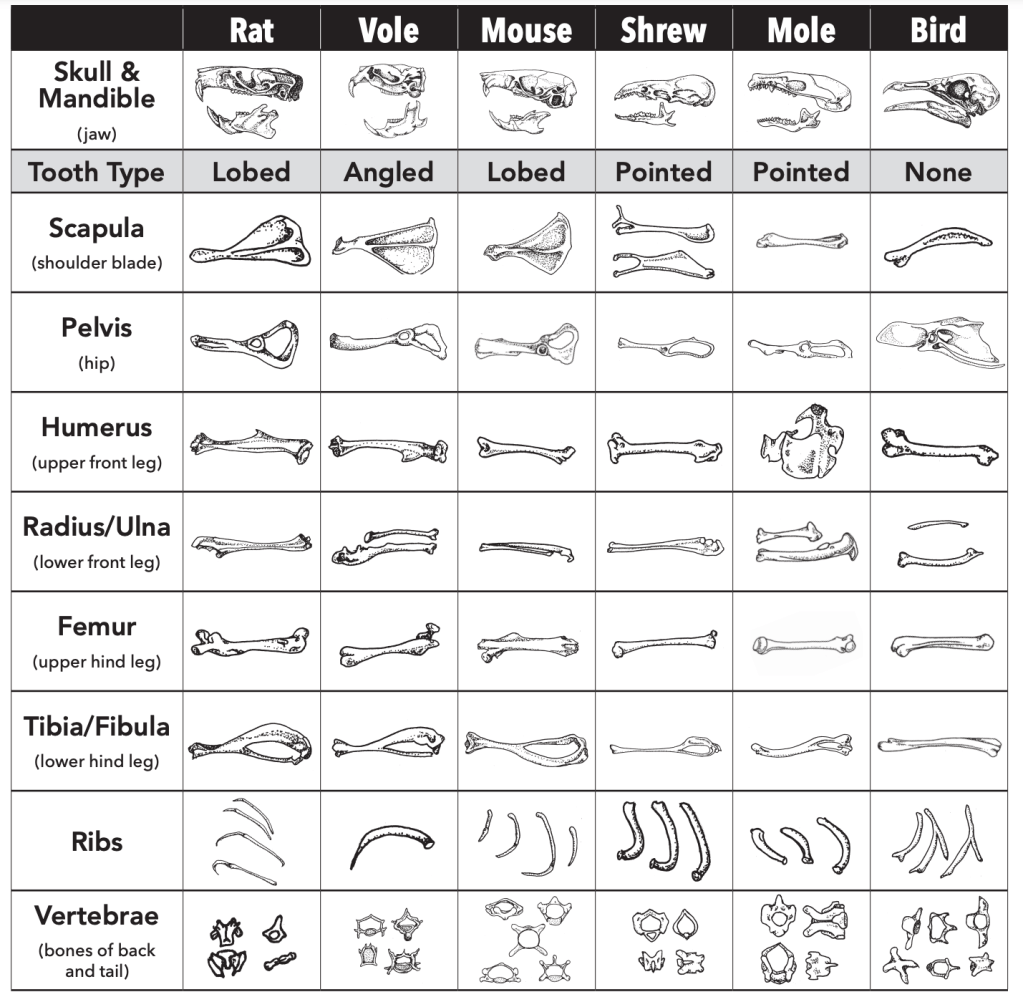

Charts like this one from the Cornell Lab of Orinthology can help students metaphorically compare the significance and scale of the content they reject; the bigger the animal or bone, the less credible the claim:

The Power of Belief

I don’t know if this might all be too much for your students. It might be, depending on their age level. But then again, it might create just the right amount of shock and interest your students need for this big idea about the believing game to stick. I can say this much: that memorable image of an owl swallowing a mouse whole helped me understand some things about the believing game I’ve missed in the past.

When we teach the believing game to students, we’re trying to extend the range of interpretive possibilities they envision. That’s the intellectual stretch the believing game gives us. It’s a rigorous method for boosting our tolerance of ambiguity and ability to postpone judgment.

There’s this too: When teachers practice the believing game with students’ ideas and arguments, we set aside our own biases while we work to understand our students’ perspectives on their own terms. I think of those students who tell me they didn’t really enjoy their high school English classes because their teachers would tell them their interpretations were wrong. Believing in our students’ intellectual powers helps us to see them–and helps our students to realize their full potential as serious and careful thinkers.

Jennifer Fletcher is a professor of English at California State University, Monterey Bay and a former high school teacher. She is the author of Teaching Arguments, Teaching Literature Rhetorically, and Writing Rhetorically.

Works Cited

Elbow, Peter. “Appendix Essay. The Doubting Game and the Believing Game: An Analysis of the Intellectual Process.” In Writing Without Teachers. Oxford University Press, 1973. 147-91.

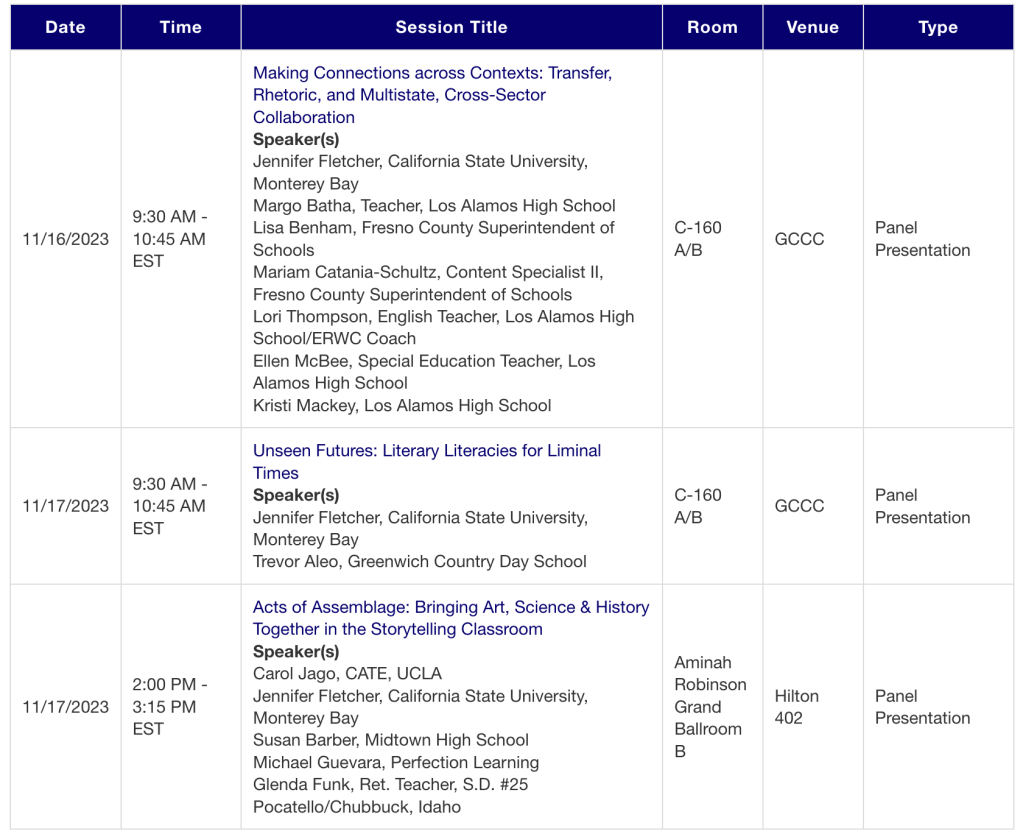

NOTE: I’m thrilled to be presenting multiple sessions at NCTE 2023. Please stop by or DM me @JenJFletcher if you’d like to chat at the convention.

This is really a digestive metaphor. The owl can eat the whole mouse because it has a digestive system that can deal with the bones one way or another. Snakes too. Coyotes too, I think. But are critical thinkers necessarily predatory carnivores? Is that really where we want to go? The believing game is a ruse, a strategy, a stance. We ask, “What if this were true?” and reason through the consequences to see where they go. It is pretend believing, an act of the imagination, a move in a game, not swallowing whole.

LikeLike

LOVE your approaches and strategies, Jennifer! Have a HAPPY THANKSGIVING!

LikeLike