By Jennifer Fletcher

I’m a big fan of home improvement shows: This Old House, Love It or List It, Good Bones–you name it, I’ve probably watched it. But my new favorite show is causing me to rethink the whole home makeover formula. Recently, I’ve been watching Cheap Irish Homes. This is the house hunting show that features “forgotten farmhouses” and “bargain bungalows,” many of which are derelict.

Here’s the thing: Cheap Irish Homes doesn’t show what these homes look like after they’ve been transformed by designers and contractors. The episodes end with the homes’ mildew stains, vine-clogged chimneys, and broken toilets still untouched.

I’ve learned from watching Cheap Irish Homes that the reveal doesn’t have to be the most important part of the story. The story can be about the process, not the end result. Maggie Molloy, the amiable host of Cheap Irish Homes, explains that the show’s purpose is to help buyers imagine new possibilities by considering unexpected options and stepping outside of their comfort zone.

That’s our purpose as writing teachers, too: to show students options and get them out of their comfort zone, so they can try new things. We don’t have to make writing instruction all about the reveal. In his blog for Inside Higher Ed, best-selling author and writing teacher John Warner says something that I just love: “When we are writing, the only thing that matters is the process. The best possible route to the best possible outcome is to ignore that the outcome even exists.” Amen. This is one of those things I know to be true in my own writing life. Put too many guardrails on my process, and I shut down.

As Warner notes, product-based writing instruction tends to dominate over process-based instruction. Our educational system, Warner says, “places much greater value not on the doing but the having done—the object, not the process.” When we focus on the product and not the process, we leave out the messy, unpredictable inquiry work that produces writing in authentic contexts.

Privileging the Before over the After

What does it look like to flip the script on writing instruction? Frankly, it can look like a hot mess. By giving students more space to do their own thinking and make their own choices as writers, we’re significantly increasing the cognitive load, and that means more frustration and confusion. These are all comments that my students have said or written in reflections.

“It’s too early in the morning for this.”

“Why are you making us do this? This is hard.”

“I don’t know what to think now.”

But instead of worrying about what the makeover will look like, let’s try embracing the mess. Let’s linger in the “before” stage as long as we need to, even if it’s uncomfortable.

Getting Out of the Way of Students’ Thinking

I still sometimes feel tempted to rush in and solve students’ problems for them when I see them struggling. However, I’m learning to resist the impulse to find the quickest way out of discomfort. And in doing so, I’m aware that I’m swimming against some powerful currents in our profession, including the new allure of AI.

There are loads of apps, formulas, and gimmicks that promise to take the stress and guess work out of writing and writing instruction. For instance, I often see these kinds of product blurbs in educational marketplaces:

- “Do your students have trouble writing paragraphs? Worry no more!”

- “This template practically writes the essay for you.”

- “Make life easier for you and your students.”

- “Work better and faster!”

- “Streamline the writing process!”

When we contract the inquiry space by giving students formulas and step-by-step instructions to follow–or when students take a similar step by using AI–their writing often looks instantly better. But I would argue that this is faux writing, not authentic rhetorical problem solving since the problem of how to respond to the rhetorical situation as been outsourced to a worksheet or app. Prematurely imposing order on writing chaos results in a cosmetic fix at best. While we may have plastered over some of the mildew stains, we haven’t dealt with the underlying structure and foundation. We have to be OK living in a fixer-upper for a while when we take a process-centered, inquiry-based approach to composition.

Embracing the Mess

When we or our students get stuck as writers, often the best way forward is to make a bigger mess. That’s right–making more of a mess, not less, helps us figure out what to say and do next. Mess is another name for inquiry. And it can look like this:

- More talking, discussion, and sharing

- More collective and individual brainstorming

- More reading and annotation

- More experimentation

- More freewriting, note-taking, and idea chunks

If we or our students don’t know where to start, we can start by talking and writing. We can take out our phones and capture some quick voice memos on possible ideas to explore or questions we have. We can write about how we’re having trouble writing. We can record a f2f or virtual conversation with a friend about what we’re trying to do. We can draw pictures and create diagrams. We can return to reading for new ideas. These strategies have all helped me get unstuck.

What has almost never helped me get unstuck? The following activities:

- Writing a thesis before I’ve written a draft or idea chunks

- Writing topic sentences

- Selecting the best evidence (I don’t know what’s “best” until I’ve written a draft and have some feedback and a fresh perspective)

These tasks force me to clean up my mess too quickly. While drafting a thesis or a topic sentence straight out of the gate might be helpful to some writers, I worry when these kinds of constraints are imposed on developing writers as the default starting point for composition.

Centering Process

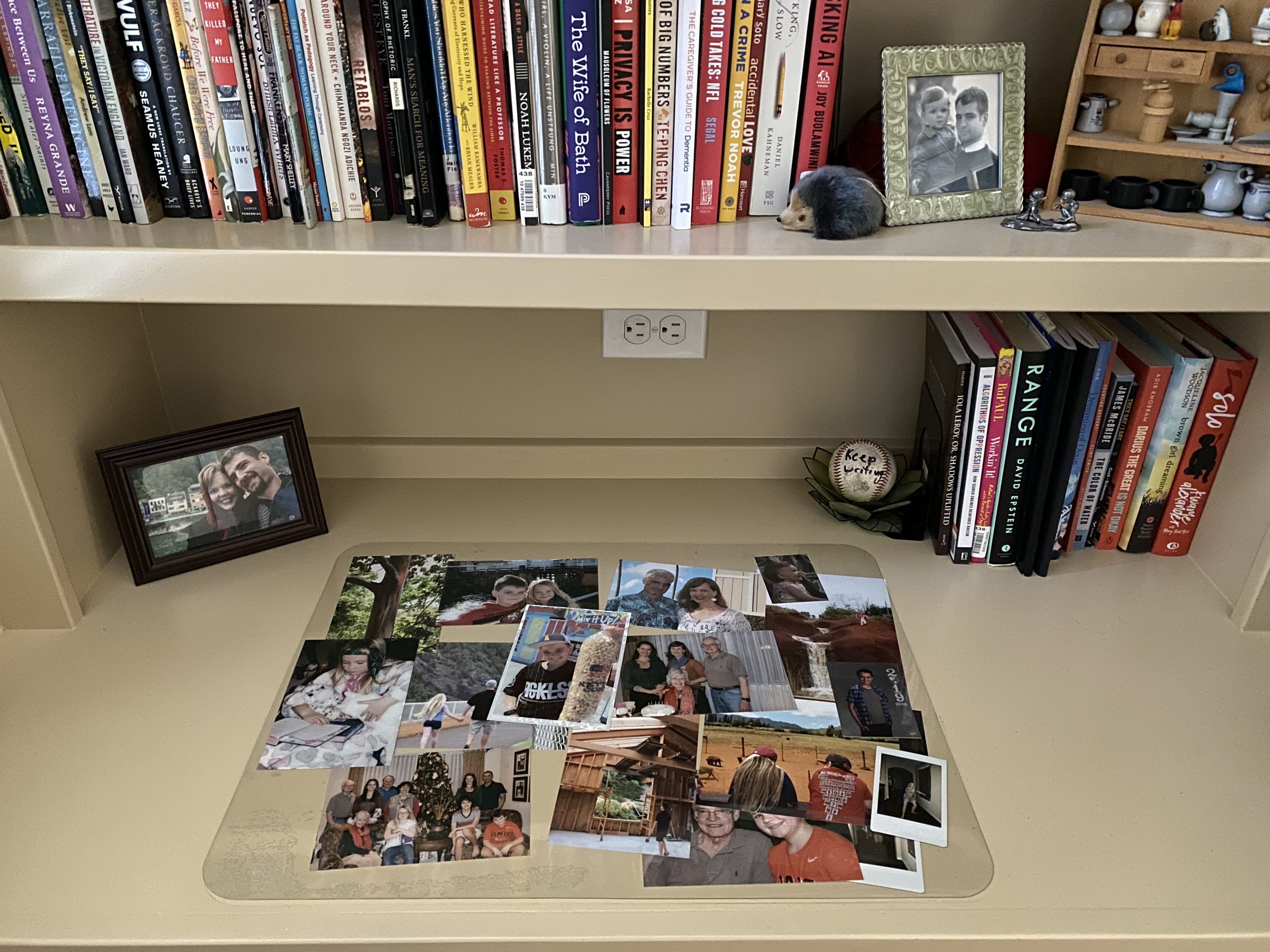

I’d like to leave you with one final before and after comparison: my desk before and after I start a writing project. Be warned: I’m one of those “If I can’t see it, it doesn’t exist” people.

This is what I always most want to learn from other writers–how they do their work, which is why my library is full of books such as Jericho Brown’s How We Do It: Black Writers on Craft, Practice, and Skill or Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: Women at Work. I guess I’m nosy. This is also why I love watching shows about homes and houses. I’m fascinated with interior life: both the life of the mind and the lives lived in private spaces.

We can change what we reveal about the writing process to our students. We can center writers’ lives and the living complexities of composition in our classrooms. Instead of spotlighting the final, polished product, let’s shine a light on the messy, unfinished work of writing in the moment. There are more important transformations that happen in a writing classroom than a quick style makeover.

Note: If you’d like to explore these kinds of ideas in conversation with colleagues, please consider registering for my spring NWP course, Teaching Argument Writing Rhetorically. See the description below.

Jennifer Fletcher is a professor of English at California State University, Monterey Bay and a former high school teacher. She is the author of Teaching Arguments, Teaching Literature Rhetorically, and Writing Rhetorically.

Works Cited or Consulted

Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, eds. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State University Press, 2015.

Bean, John C., Virginia A. Chappell, and Alice M. Gillam. Reading Rhetorically. 4th ed. Pearson, 2014.Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State UP, 2007.

Hammond, Zaretta. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin, 2015.

National Research Council. 2000. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. National Academy Press, 2000.

Slomp, David, Rita Leask, Taylor Burke, Kacie Neamtu, Lindsey Hagen, Jaimie Van Ham, Keith Miller, and Sean Dupuis. “Scaffolding for Independence: Writing-as-Problem-Solving Pedagogy.” English Journal 108.2 (2018): 84-94

Warner, John. “The Writing Is What Matters.” Inside Higher Ed. 01 Feb. 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/blogs/just-visiting/2024/02/01/process-all-learning-through-writing.

Did you know that The National Writing Project is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year? As a long-time admirer of this premier professional organization for the teaching of writing (and a child of the 70s myself), I’m delighted to be part of the festivities. This spring I have the privilege of facilitating a course on teaching argument writing for NWP. Please see (and share!) this flyer. Interested teachers can register for the course here. The registration fee includes individual or group coaching. Consider registering as a site team to receive an included group coaching session.

Course Description

A rhetorical approach to argument writing cultivates adaptive, independent learners who can analyze and compose texts in diverse situations. In this four-week course, author and teacher Jennifer Fletcher provides strategies and frameworks for taking argument writing to the next level by developing students’ rhetorical problem-solving skills. These include the inquiry and reasoning skills that help learners communicate and collaborate across contexts. Special attention is given to rhetorical concepts—such as audience, purpose, context, and genre—that help writers adapt to new situations. Using examples from Jennifer’s book, Writing Rhetorically, participants in the course examine and design instructional activities that foster inquiry-based argumentation and rhetorical decision-making. Participants will leave the course prepared to support students in making their own informed choices as thinkers and writers.

There is a six-week break between Week Two and Week Three of this course to allow participants time to apply and reflect on their learning.

Participants receive:

- Four real-time virtual workshops with author and teacher Jennifer Fletcher

- A print copy of Writing Rhetorically: Fostering Responsive Thinkers and Communicators

- Digital study guide and appendixes for Writing Rhetorically and Teaching Arguments

- Activities and graphic organizers for teaching audience, purpose, genre, and structure

- Support for teaching evidence-based reasoning, synthesis, and claim development

- A digital badge indicating completion of twenty learning hours

- The opportunity to earn CEUs from Cal State Monterey Bay

Course Notes:

- This course will run for 2 weeks in March and 2 weeks in May:

- March 3 – 16, 2024

- Real-time events: March 6th and March 13, 4-5pm PT | 7-8pm ET

- May 5 – 18, 2024

- Real-time events: May 8th and 15th, 4-5pm PT | 7-8pm ET

- March 3 – 16, 2024

- 1 hour of synchronous and 4 hours of self-paced learning per week for a total of 20 hours